IFS – Increasingly Fewer Slots

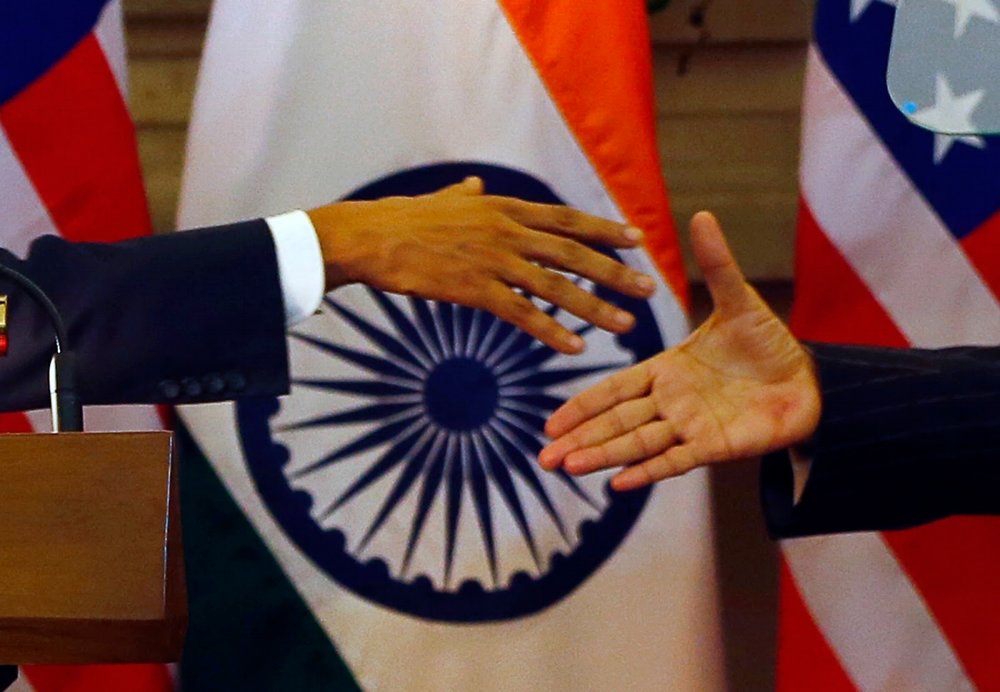

Today, India is no longer content with being labeled the diplomatic version of a U.S. college waitlist called the “regional power” – that is, a way of politely telling a country that they are good, but not good enough. Especially with the arrival of Narendra Modi, Indians have started dreaming of the day when scholars speak of a “Pax Indica”, and perhaps even the day when India joins the United Nations Security Council as a permanent member.

But curiously, India’s vehicle to global recognition - the Indian Foreign Service - does not have the fuel to carry these grand ambitions forward. Since its inception, the Indian Foreign Service has been an organization that has not received the resources and personnel it needs to represent a country of India’s magnitude. In total, the IFS has less than 800 class one officers, to represent a country of over 1.3 billion people (with 2700 people of diplomatic rank in total). That means each IFS class one officer represents more than 1.6 million people – that’s equivalent to having one such officer for the entire country of Bahrain. India’s diplomatic corps is smaller than Brazil’s whose population size is 15% of India’s. Furthermore, of the almost 500,000 people who give the civil services examination every year, the IFS selects no more than 30-35 candidates to join the diplomatic corps. That means an acceptance rate of 0.006% to an already understaffed diplomatic corps. If India truly aspires to become a significant global player, it needs to scale-up its foreign service. Along with expanding the annual Union Public Service Commission examination intake in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, India needs to make it easier for people to make a lateral entry into the foreign service. It needs to become easier to transition into the foreign service from areas such as universities, think tanks, and the private sector because each of these offers a wealth of experience and knowledge that is tough to get from examination recruits alone.

To do this, the government can start by making the IFS a more lucrative job option. It is telling that none of the top 10 candidates in the 2015-16 UPSC examination opted for the IFS – in fact, the IFS topper was ranked 14th, followed by 24th, with the last being 114th. With more alternative opportunities to travel and live abroad than ever before, the luster of embassy work and diplomacy has quickly declined, and the IFS will have to find a new way to brand itself.

Additionally, India needs to work on training candidates and ensuring that they are qualified for these positions. Although complaints about the quality of officers are rare – the IFS is generally known for its efficiency and tact – this may change with an increase in recruiting. One way to do this is to test for qualities more specific to foreign service, either by introducing a separate section of the UPSC exam for IFS aspirants, or by creating a whole different foreign service recruitment process, as it is in the United States and several other countries. The fact that the foreign service and the police service have the same exam is indicative of the fact that the UPSC exam, with its 23 services, needs to be more streamlined to meet the individual needs of each service.

Nonetheless, all is not bleak when one considers the future of the Indian Foreign Service. With the Standing Committee on External Affairs’ Expansion Plan of the Foreign Service, things finally seem to be moving in the right direction. Perhaps Narendra Modi’s robust foreign policy aims and the galvanizing effect it has had on India’s population will do some good too, with the IFS incentivized to recruit more people and more people interested in foreign service. What the current administration needs to acknowledge, however, is that Modi’s visionary foreign policy cannot fly on the strength of its vision alone. The recent Doklam standoff highlighted the crucial role that Indian diplomacy has to play in resolving conflicts. This importance is only going to increase with India’s rise and power, and it is the government’s job to make sure the IFS is ready for it.

Harsh Dubey is a staff writer at India Ink. You can reach him at [email protected].